| Study | Effect expected | N | Trials | M | SD | Hits (%) | t | p | ES | Var | BF | Direction | Year | Lab/Online |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

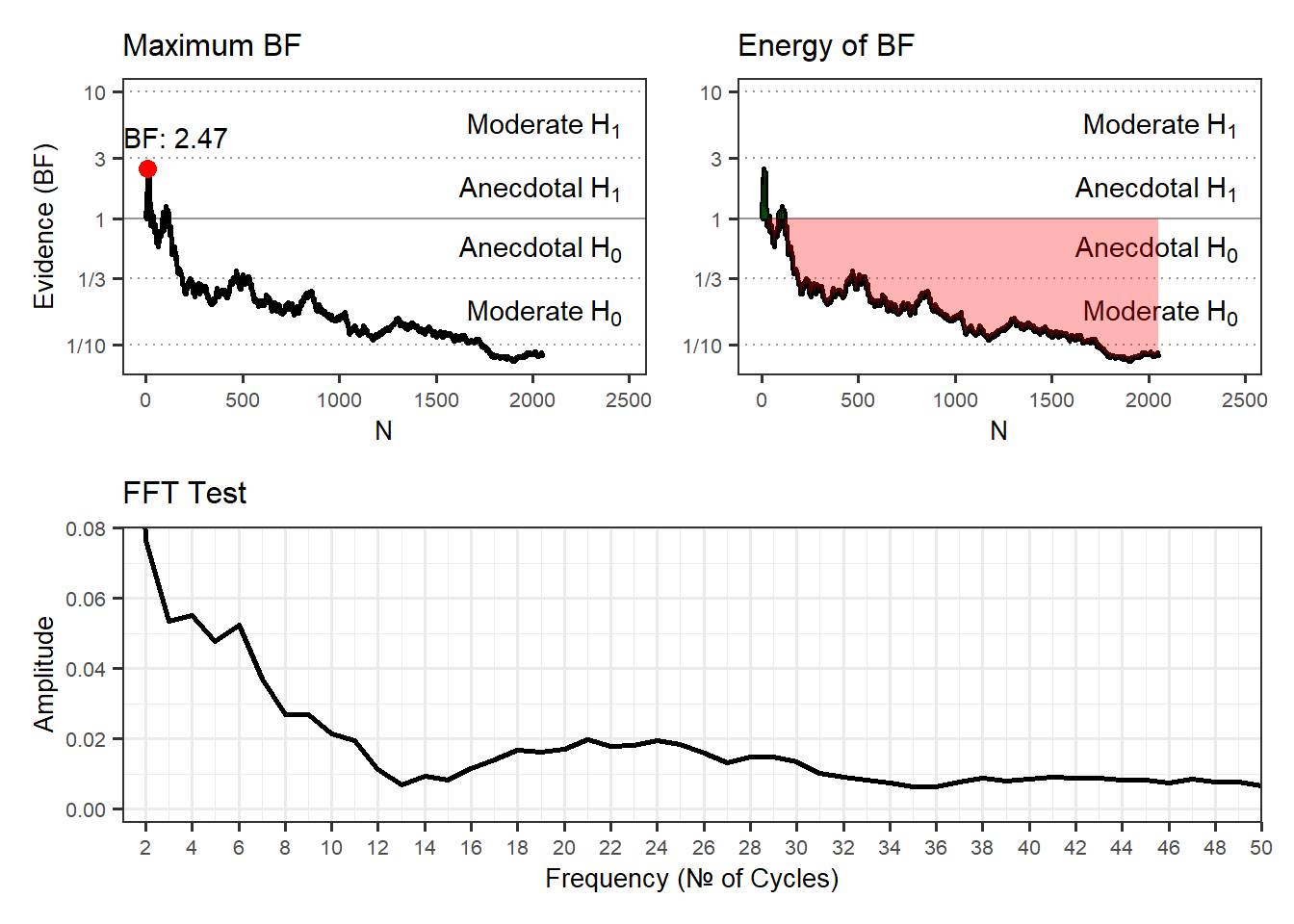

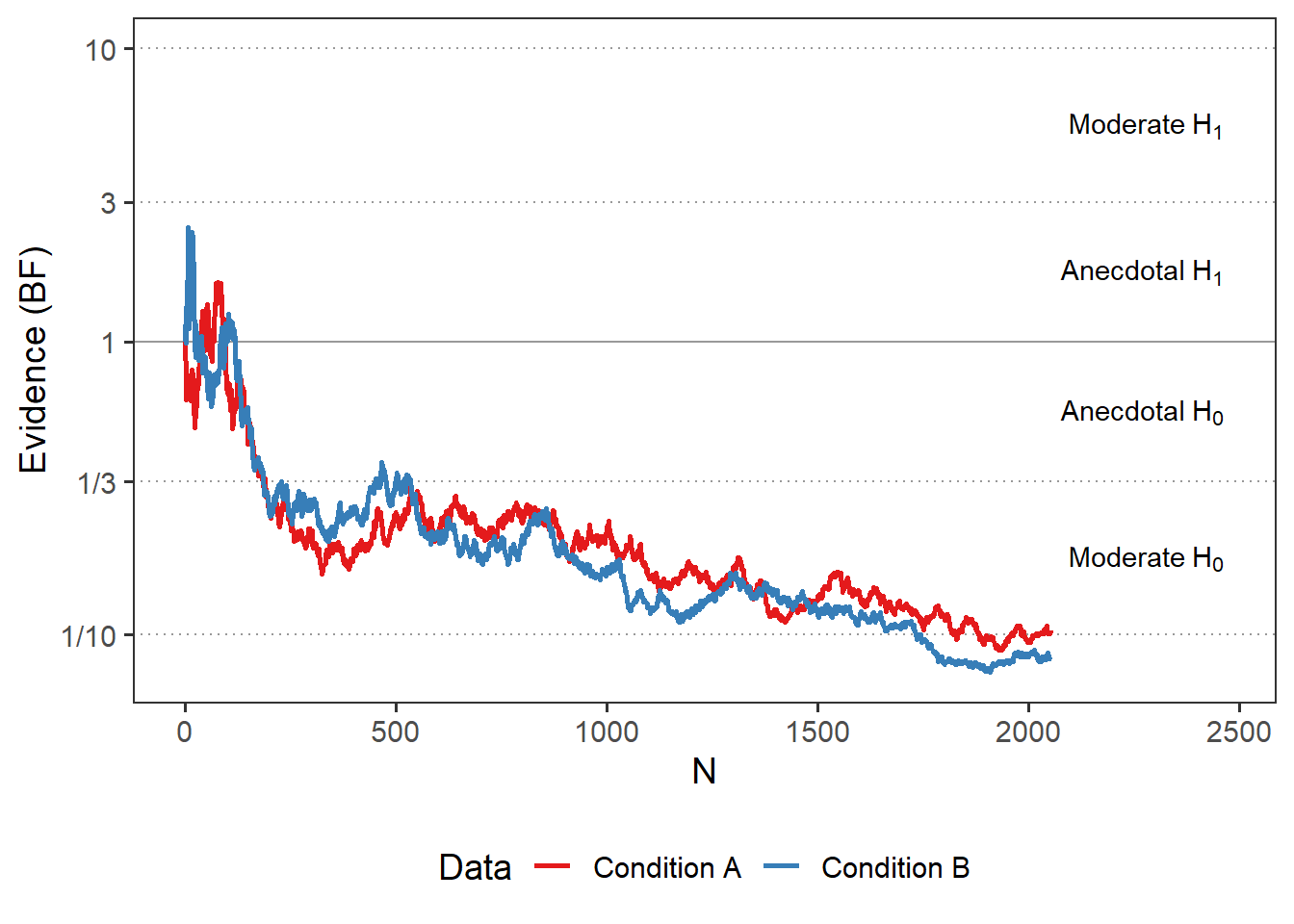

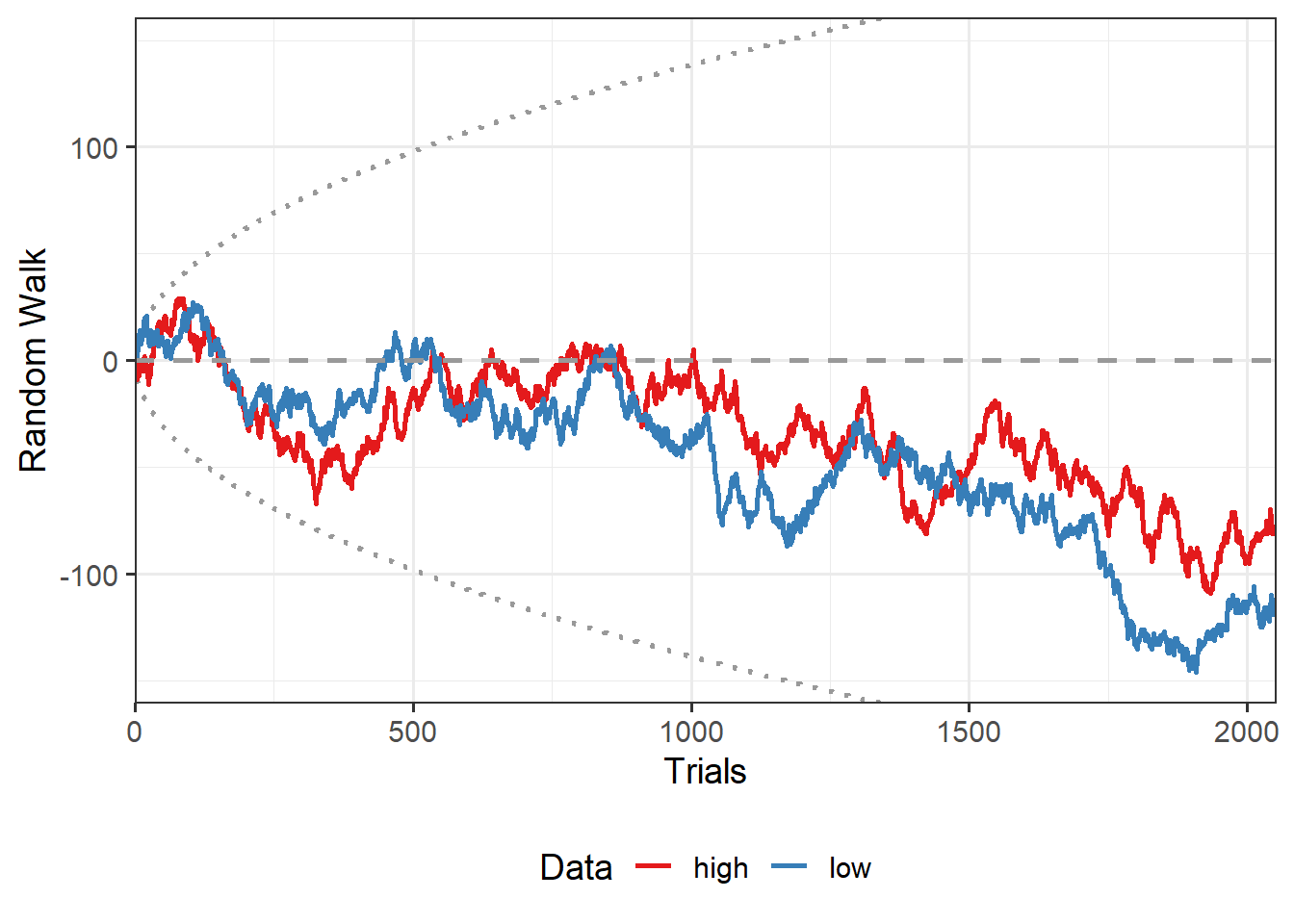

| Epsi Correlation Condition A | ✖ | 2052 | 20 | 9.96 | 2.26 | 49.81 | -0.75 | 0.77 | -0.02 | 0 | 0.10 | greater | 2021 | 🌍 |

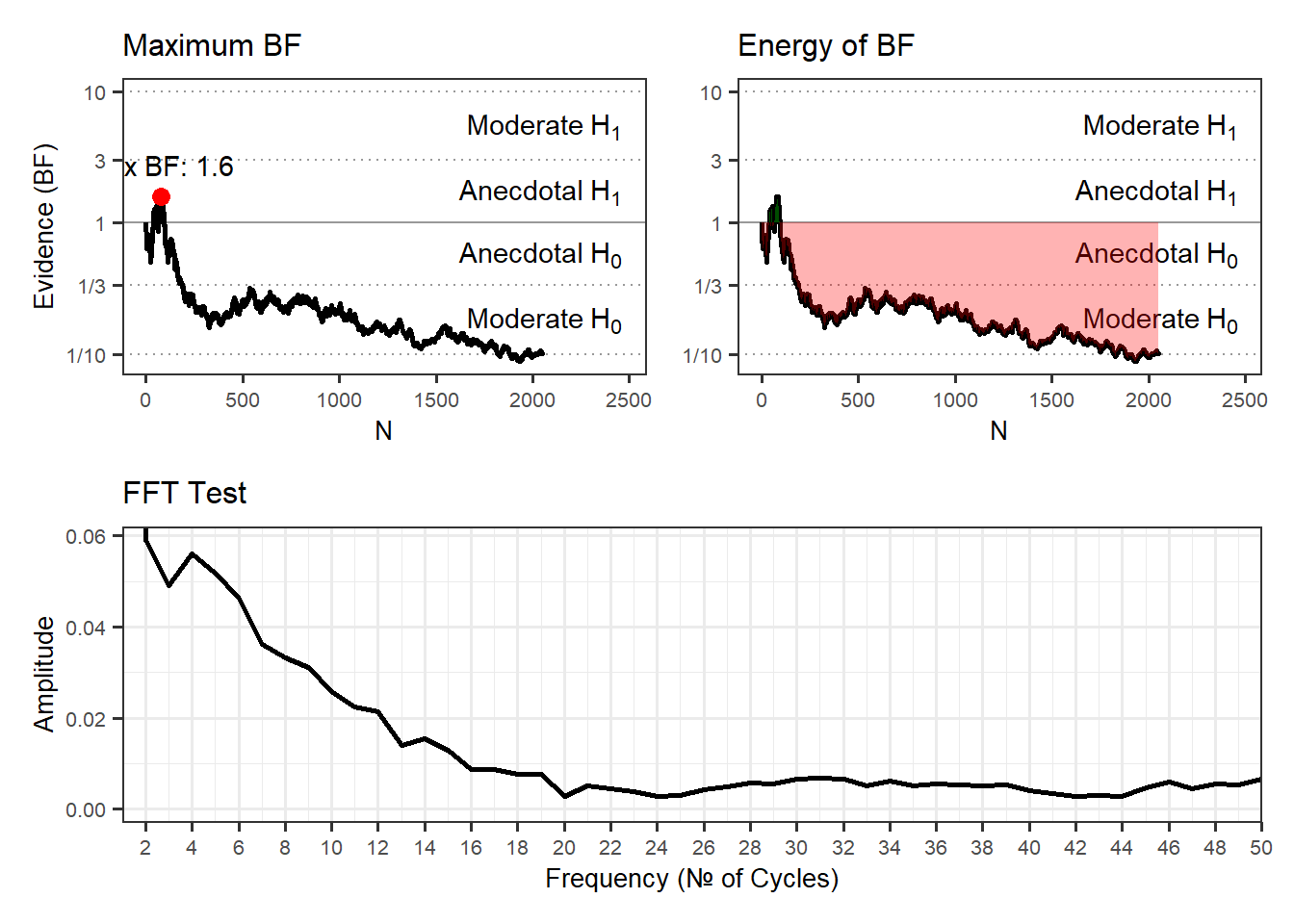

| Epsi Correlation Condition B | ✖ | 2052 | 20 | 9.94 | 2.26 | 49.72 | -1.14 | 0.87 | -0.03 | 0 | 0.08 | greater | 2021 | 🌍 |

Epsi Correlation

Design and Hypothesis

Original Study Design and Hypotheses

The study was initially designed as a preregistered replication of (Dechamps et al., 2021) micro-psychokinesis research (see priming studies), which had found intriguing patterns across three studies. The original research used subliminal priming to test whether participants could unconsciously influence quantum random number generators to select positive images more frequently.

Hypothesis: We expected to replicate a strong correlational effect (r = .032, BF10 = 36.46) between experimental and control conditions that had been found in a post-hoc analysis of the combined data from Dechamps et al.’s three studies. We predicted this correlation would appear specifically when standard micro-PK effects were absent, representing a stable relationship between the two conditions.

The Critical Discovery

However, after data collection and analysis were complete, we discovered that the original correlation effect they were trying to replicate was based on a coding error in the original dataset. Eight participants in Study 3 had been incorrectly coded with negative values, and when this error was corrected, the strong evidence for correlation completely disappeared (r = -.01, BF01 = 49.48).

Transformed Research Question

This discovery transformed the study from a planned replication into an unintentional exploration of experimenter effects in micro-PK research. The new research question became: Would experimenters’ strong but false expectations about a correlation effect actually influence the appearance of such an effect in the data?

This addresses a fundamental concern in micro-PK research - that experimenters’ beliefs and expectations might unconsciously influence quantum-based outcomes, making it difficult to distinguish between participant effects and experimenter effects. The study thus became an anecdotal field experiment examining whether purely subjective experimenter expectations, contradicting objective reality, could manifest as measurable effects in micro-PK data.

Participants

| Characteristic | Count/Statistic |

|---|---|

| N | 2052 |

| Female | 49.03% |

| Male | 47.71% |

| Mean Age | 44.22 years |

| SD Age | 13.84 years |

Materials and Procedure

Materials and Procedure were identical to the priming studies.

Sample Size and Data Analysis

We employed Bayesian inference statistics to test the hypothesis, which allow for sequential data accumulation until specific stopping criteria are met. For the correlation effect analysis, we used a Bayesian correlation test with a stopping rule of BF = 10 (indicating strong evidence for either the null or alternative hypothesis). If this criterion wasn’t reached by approximately 1,000 participants, data collection would continue if a clear trend toward BF10 = 10 was observable.

The correlation analysis used a Beta (0.1) prior distribution based on an estimated effect size of r = .1, which had been previously applied in analyzing the original faulty correlation data from Dechamps et al. (2021). For standard micro-PK effects, we conducted separate one-sample Bayesian t-tests for experimental and control conditions using one-tailed approaches with informed priors centered around 0.05 (δ ~ Cauchy [0.05, 0.05]). Interestingly, we expected and hoped for null findings, as the absence of standard micro-PK effects was considered a precondition for the correlation effect to appear, consistent with their preregistration.

The Bayesian analyses were performed irregularly during data collection, approximately weekly for the first 1,000 participants and then again with the complete sample of over 2,000 participants, using R’s ‘Bayes Factor’ package. Data collection occurred between January and February 2021.

Regarding sample size, although the stopping criterion of BF10 = 10 for the correlation effect was reached early at n = 24, we considered this subsample too small to provide convincing evidence and continued until reaching 1,000 participants. At this point, the correlation was r = .034 (similar to the original r = .032), but the Bayesian evidence remained inconclusive (BF10 = 0.42). Following the preregistration, we collected data from an additional 1,000 participants before stopping due to exhausted financial resources. The final sample included N = 2,052 participants.

Lab Report Data

No micro-PK effect is expected in both conditions.

Results of Universal Micro-PK Hypothesis

Condition A

Condition B