| Study | Effect expected | N | Trials | M | SD | Hits (%) | t | p | ES | Var | BF | Direction | Year | Lab/Online |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Priming 4 Exp | ✔ | 4060 | 20 | 10.0 | 2.19 | 49.98 | -0.13 | 0.55 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.08 | greater | 2020 | 🌍 |

| Priming 4 Con | ✖ | 4060 | 20 | 9.9 | 2.26 | 49.52 | -2.69 | 1 | -0.04 | 0 | 0.03 | greater | 2020 | 🌍 |

Priming 4

Hypothesis

The preregistered study was a conceptual replication of Study 3, testing the Model of Pragmatic Information (MPI) (Lucadou et al., 2007). The MPI predicts that initial evidence for an effect will decline over time, with non-random oscillations not replicable in a direct replication study but potentially reappearing in a conceptually different study. The study aimed to reappear the effect in the experimental (positive priming) condition, with potential decline over time.

Participants

| Characteristic | Count/Statistic |

|---|---|

| N | 4060 |

| Female | 49.29% |

| Male | 46.75% |

| Mean Age | 46.25 years |

| SD Age | 12.86 years |

Materials

The experiment replicated the previous studies with a nearly identical setup, except for modifications in the priming procedure and the stimuli used for primes and targets to conduct a conceptual replication instead of a direct one.

The stimuli comprised images from the Pictures of Facial Affect by Ekman and Friesen (Ekman & Friesen, 1976), which includes 110 photographs of 14 actors showing various emotional states. For this study, images depicting happiness, anger, and neutral expressions were selected, resulting in 14 sets of three images each. The principal investigators chose these expressions because they are the most aversive (angry faces) and most appetitive (happy faces) to human observers. Scrambled versions of neutral faces served as masks in the priming procedure, leveraging established effectiveness in subliminal processing of facial expressions.

Procedure

A design similar to previous studies was used, involving 20 experimental (positive priming) and 20 control (neutral priming) trials presented in random order. Participants saw masked neutral facial expressions as primes in the neutral priming condition and masked happy facial expressions in the positive priming condition.

Participants were recruited via email by Kantar, a polling company, and directed to the study hosted on an LMU web server. After enabling full-screen mode, they provided demographic information and began the experiment. A pseudo-RNG determined the trial order and conditions, with trials randomly assigned to positive or neutral priming conditions. Each participant experienced 40 trials, with stimulus sets selected from 14 available sets via sampling with replacement.

The procedure for each trial involved displaying a fixation cross (1200 ms), a forward mask (160 ms), a prime (40 ms), and a backward mask (200 ms), repeated three times with the same prime. Neutral or happy primes, masks, and target faces were matched and derived from the same actor. A qRNG then determined whether a happy (“0” bit) or angry facial expression (“1” bit) was displayed as the target stimulus for 1000 ms. Each trial was followed by a black inter-trial interval (1200 ms).

After all 40 trials, participants rated their perception of friendly faces as positive and angry faces as negative on a seven-point scale and indicated their overall feeling of success for the day. Finally, they were thanked and directed back to the polling company for a short debriefing.

Sample Size and Data Analysis

The analysis strategy for this study followed the same approach as Study 3, focusing on changes in evidence using sequential Bayes factors (BFs) from two Bayesian one-sample t-tests (one-tailed) on the raw data (mean of positive pictures) from the positive and neutral priming conditions. Due to the anticipated volatile effect, a fixed BF threshold could not be used as a stopping criterion. Based on the positive results of Study 1, the pre-registered target sample size was around 4,000 participants.

Data collection was conducted by Kantar between February and March 2020, with about 100 participants recruited per day. The final sample consisted of 3,996 participants (with demographic data for 3,951 participants). Once the target sample size was reached, data collection was halted, and the data were analyzed.

Results of Universal Micro-PK Hypothesis

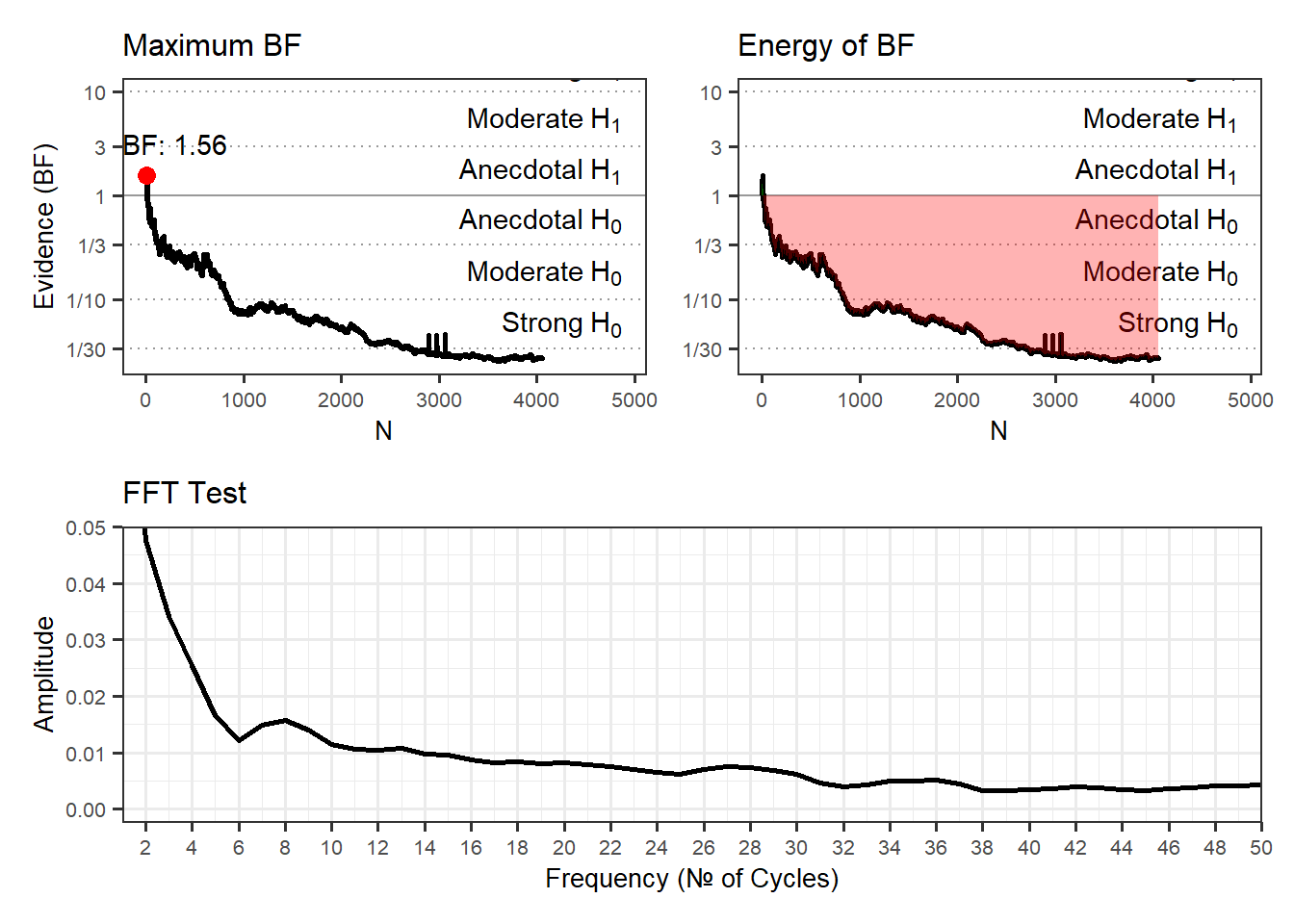

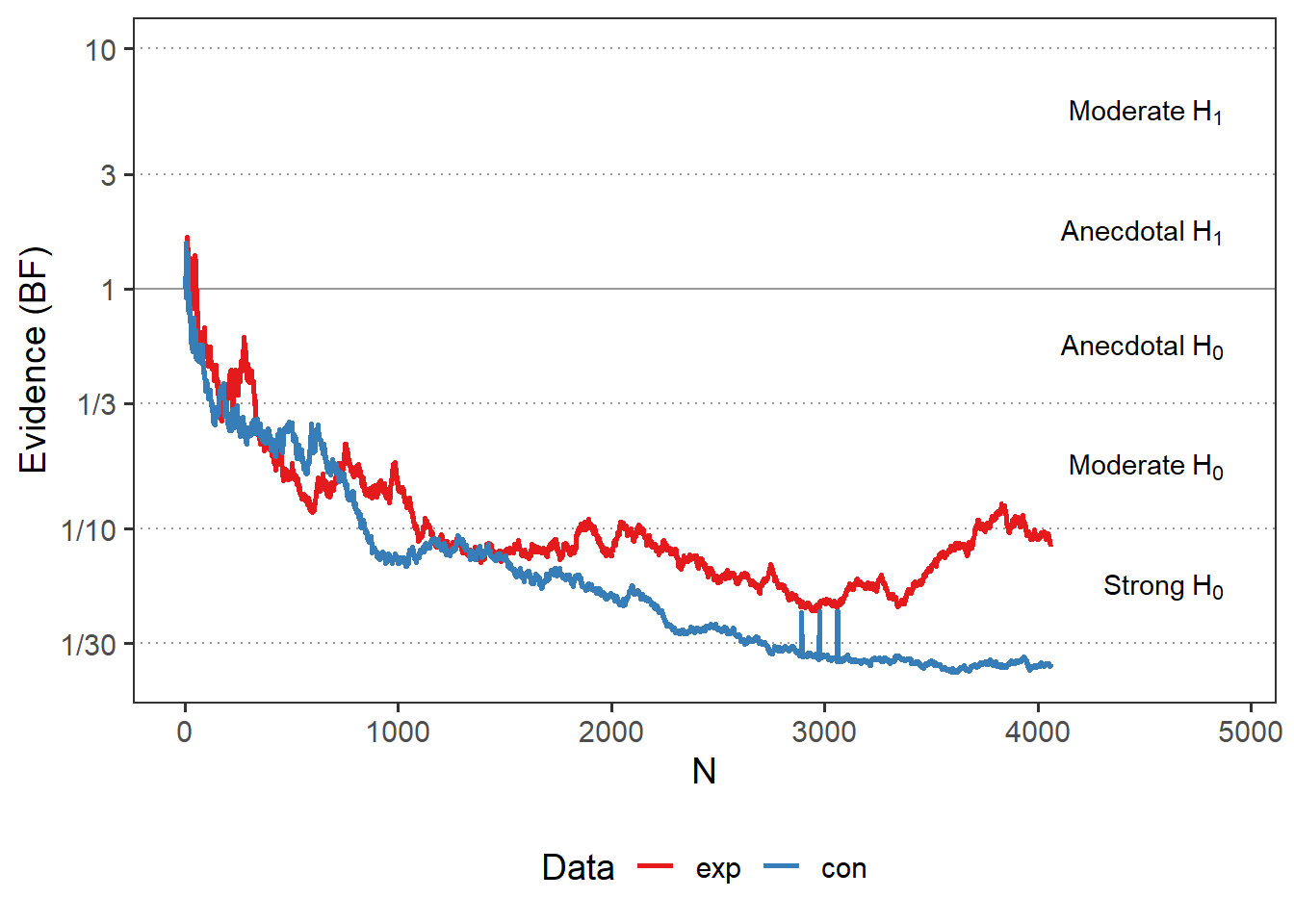

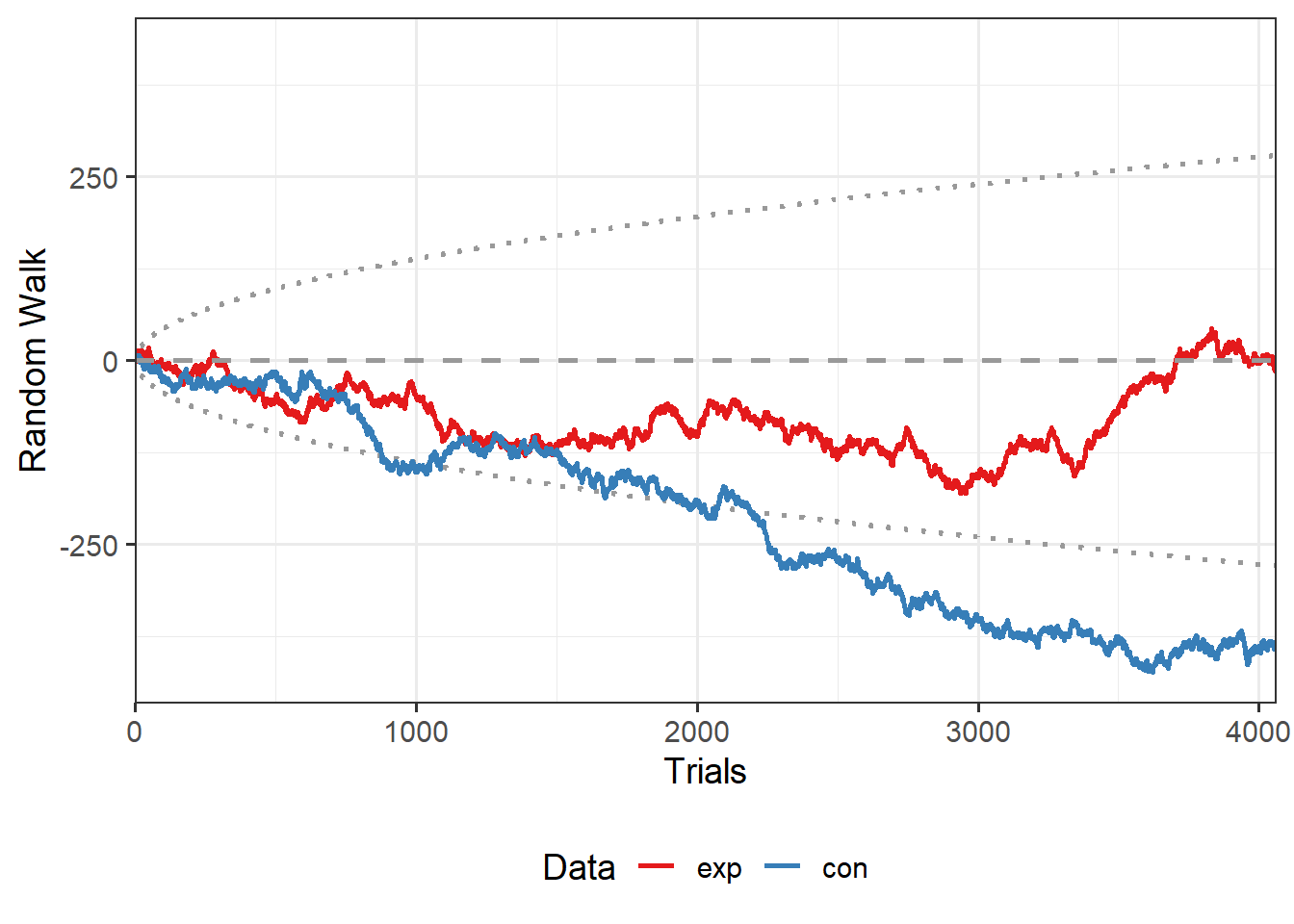

Exp

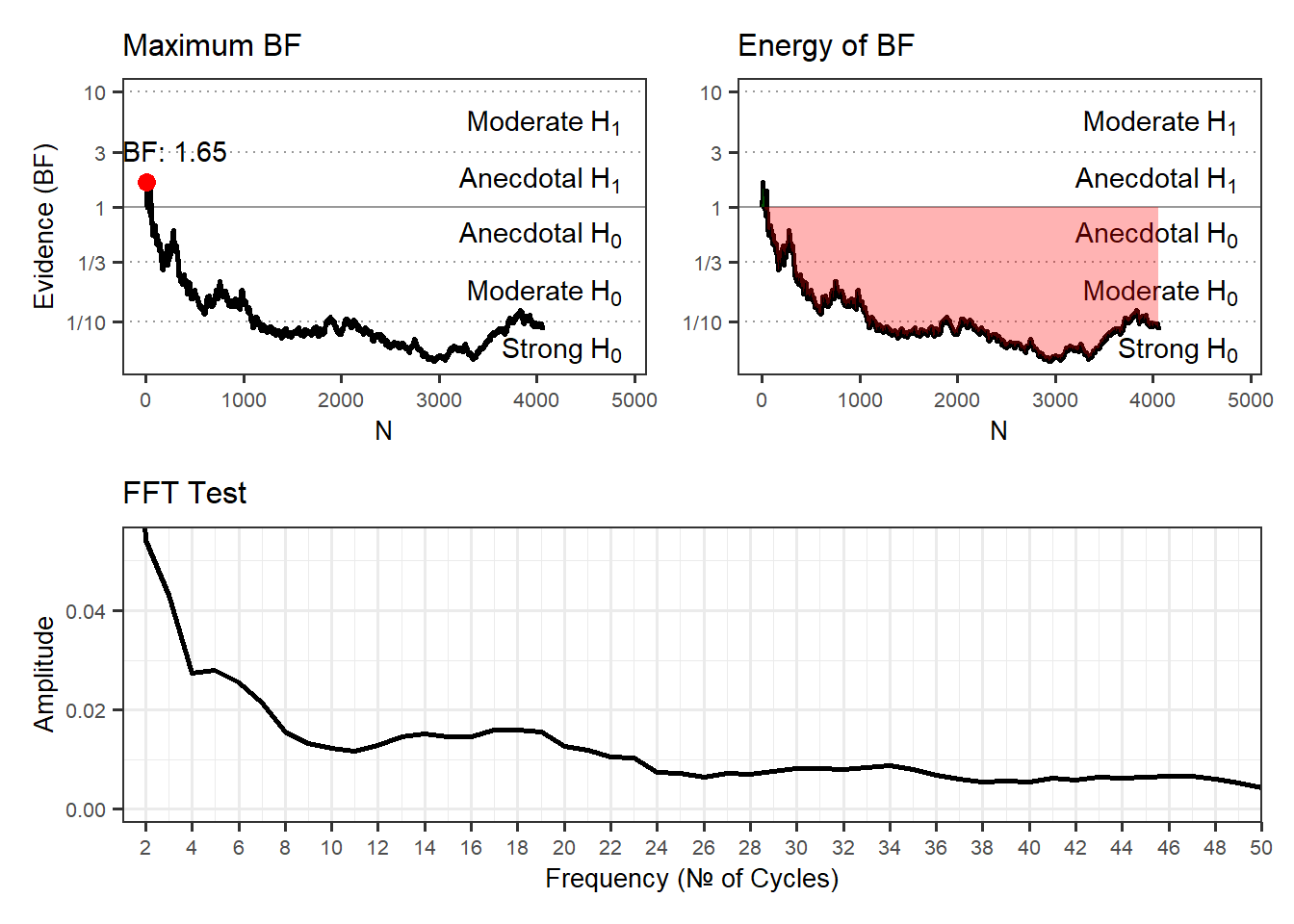

Con